- Home

- Charlotte Mendel

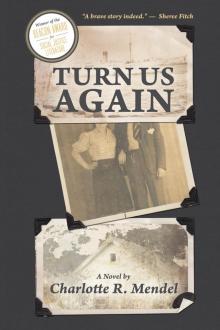

Turn Us Again

Turn Us Again Read online

TURN US

AGAIN

TURN US

AGAIN

A Novel by

Charlotte R. Mendel

Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

Halifax & Winnipeg

Copyright © 2013 Charlotte R. Mendel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher,

except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Editing: Linda Little

Copyediting and text design: Brenda Conroy

Cover design: All Caps Design

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

This book is based on a true story.

Published in Canada by Roseway Publishing

an imprint of Fernwood Publishing

32 Oceanvista Lane, Black Point, Nova Scotia, B0J 1B0

and 748 Broadway Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3G 0X3

www.fernwoodpublishing.ca/roseway

Fernwood Publishing Company Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Nova Scotia Department of Tourism and Culture and the Province of Manitoba, through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, for our publishing program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Mendel, Charlotte R., 1967-, author

Turn us again / Charlotte R. Mendel.

ISBN 978-1-55266-570-1 (pbk.)

I. Title.

PS8626.E537T87 2013 C813’.6 C2013-902992-3

CONTENTS

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ONE

Once upon a time, I loved flying Air Canada from Nova Scotia to London. Widely smiling stewardesses with perfect teeth greeted you at the entrance to the plane, slinging your heaviest baggage into the overhead bins, their smiles unwavering even as they staggered under the weight. Within minutes they were bombarding you with newspapers, headsets, mints to suck during take-off. As soon as the plane levelled off in the sky they’d come trotting around with their drink-and-snacks trolley.

Back when the service was decent, I used to have two gin and tonics accompanied by a cigarette, rounding it off with wine when my meal arrived. Alcohol affects you differently at high altitudes; a pleasant numbness takes over. I’d wiggle my hands to feel my toes and smile like an idiot into my drink, anticipating the next round of sensuous gratification. People who malign airline food flabbergast me. Little surprises in each box — an hors d’oeuvre consisting of a salmon roll with cheese inside, a cherry cake in the dessert box, a chocolate hidden between the sugar and cream for your coffee. Bliss and luxury.

But now it has all changed. Of course you can’t smoke anymore, but you can’t smoke anywhere anymore. It’s the constant corner-cutting — nothing’s quite as good as it used to be because everybody’s trying to save a buck. They don’t offer you gin, only wine, their pursed lips conveying disapproval when you ask for another. Perhaps it’s all the new regulations, which the stewardesses love to enforce because air-borne rules differentiate them from land-bound waitresses.

This flight is probably going to be ruined by the kid. At first I am devastated to be sitting next to a mother and toddler. I want neighbours like statues who pee infrequently and ignore me. But once the flight is underway I kind of get used to the kid. It beams up at me, often, and doesn’t mind when I ignore it. It shows me a teddy bear and informs the side of my head that the bear’s name is Bee-Bee. The kid can’t talk very well, so communication consists of waving the bear around and saying ‘Bee-Bee’ about fifty times. This might have been annoying, but somehow the one-tooth grin makes it amusing.

The kid is full of beans. As soon as the seatbelt sign is switched off it’s running up and down the aisles, stopping to radiate joy towards other kid passengers. This bugs the stewardesses. First they tell the mother that it should remain sitting at all times. This would entail holding a screaming, protesting, wriggling child by force for the entire flight. Then they want her to put shoes on it. Then they want her to keep it out of the galley.

The mother wants the kid to sleep, probably because it’s a night flight and way past Junior’s bedtime. The kid drinks a bit of milk from her breast, then releases it with a great smack and looks at me, willing me to make eye contact, emitting a milky burp in my direction. It begins to make insistent demands to get down, while the mother looks exhausted and frantic. At last, at around 11:30 p.m., the kid sprawls out on the empty seat between us and sleeps. Waves of relief emanate from Mum.

An officious stewardess comes bustling along and says the kid must sit on the mother’s lap because we’re passing through some turbulence. She gestures impatiently to the seat belt sign over our heads, which turned on about a second ago.

“He’ll wake up,” cries Mum in despair.

“I’m sorry, but those are the rules. It’s for your child’s safety.”

“But he has his seatbelt on. If there’s a lot of turbulence I’ll pick him up, I promise. Please, please, let him stay where he is for now at least.”

The stewardess leans forward with a knowing expression on her face. “I’ve seen kids shoot up and smash against the ceiling like broken eggs,” she says. “There are rules for a reason. Kids under two must sit on their mother’s laps, facing them.”

“He’s two next month! He’s big for his age, he’s as big as a thirty-month old!”

“I’m sorry,” says Glorified Waitress, with an ingratiating smile that says, I’m really a nice Canadian at heart.

The kid wails for an hour straight. The mother is distraught. I can’t watch my film or go to sleep, but instead of feeling murderous towards the kid, who looks so miserable, I silently berate the stewardess. I think up entire speeches in my head, eloquently putting her to shame.

I become aware that my internal monologue is causing facial spasms, which might make the poor mother nervous. So I rearrange my face into its usual unwelcoming grimace and think instead about my father, whom I haven’t seen in about twenty years. The reason I’m on this flight today is because of his fax. It just said:

Dying, would like to see you again.

And my first thought was, oh fuck, what timing. In the middle of a huge project at work, finally in a half-way decent relationship. Concentrating on the need to buy time, I sent a reply within minutes, without thinking:

Dying right away or in process?

My girlfriend Jenny had a fit.

“Are you joking? Tell me that’s an example of your awful sense of humour.”

“You think my sense of humour is a

wful?” This was news to me. I’d always thought that I was pretty funny, and that she thought so too.

“It’s your father. Your father!”

“I haven’t seen him since my mother died.”

“Even if you were writing to a complete stranger, your answer is insensitive.”

Jenny’s face was all serious, as though my fax reflected an important part of my character that she hadn’t discovered before, that might affect our future together. This often happened with her, and I found it boring. At the same time I wanted to wipe that self-righteous look off her face.

“He’s an alcoholic and we … we had a problematic relationship.” I meant to awaken the feminist side of her nature, but a gooey side erupted instead. I was forgiven, so contritely that I wondered whether I should have saved the information for a more serious travesty. Would it have worked for a bit on the side, for example? ‘I’m so sorry. My subconscious is forcing me to cheat on you in order to destroy our relationship because I am frightened at how important you are becoming … you see, my parents’ relationship…’

Jenny sat on my knee, stroked my hair, asked me to tell her all about it — open up, get it off my chest. Maybe a smidgen of how-come-you-never-told-me-before-you-bastard-I-thought-we-were-soulmates.

There was nothing I could say that wouldn’t make my first sentence an anti-climax, so I just shook my head and hinted that I really, really didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t remember much in any case — a sense of anxiety that always permeated the house, my anger when my mother died suddenly of a heart attack. Who remembers why I was so angry? It would be almost twenty years ago now. Soon after her death, I’d left home at the tender age of eighteen and never gone back. There had been a few letters, especially at first. Two, three years after my mother died my father told me that he was returning to England. When I graduated from university with honours I wrote to let him know — I knew it would please him — and he sent me a cheque to pay off my student loan. We sometimes sent each other postcards when we travelled. It’s funny how that happens. I guess I just went on with my life, and didn’t think about him too much.

Jenny persuaded me to send another fax right away, and then left me to get on with it, casting sorrowing glances over her shoulder as she walked out the door.

I sat there twiddling my pen. I couldn’t think what the hell to write. I felt uncomfortable all of a sudden, and wished that I could unwrite the previous fax. Shame overwhelmed me as I pictured my father receiving it. A large, powerful presence, a red curly beard. Would he feel contempt? ‘Stupid, selfish boy.’ Would he feel impotent anger, sorrow? Because nobody loved him. I couldn’t believe how wretched these thoughts made me feel. Was this Jenny’s influence, or some ancient patriarchal thing extending its claws from the past?

Apologize for previous communication. Terribly sorry to hear of your troubles. Can come end of April. Is that OK?

And within an hour I had my answer, which let me know that he had been hovering over the fax and had not answered my first flippant effort on purpose.

Only in process of dying. End of April fine.

Wonderful, the end of April would allow me to wrap up loose ends at work, cast around on the web for the cheapest ticket possible, and take Jenny out for the evening. A nice meal and perhaps a play would, I hoped, compensate for the fact that I planned to spend the majority of my yearly vacation travelling around England, under the guise of mending ancient rifts with Dying Dad. It was foolproof — who could be so selfish as to complain about that? Not Jenny. On the few occasions when we travelled together, she liked to visit art galleries and museums, absorbing the history of the place, while I wanted to sample different foods and hobnob with other tourists and couldn’t care less about culture. Only authentic-looking restaurants would do, which meant they didn’t sport the bright, clean atmosphere of your average Canadian restaurant. Jenny was convinced ethnic food would kill her, and pushed for bland, tourist-oriented hotel fare. Each travelling day was fraught with irreconcilable differences. I yearned to travel solo.

Jenny also doesn’t realize that whatever is expected of me in this final meeting, I’m not up to it. I can’t bear the thought of unremitting interaction with the stranger that is my father. I’m being selfless going at all — a day or two at the deathbed will more than suffice. Then I can spend a few weeks exploring. It has been years since I visited England, and I’ll enjoy traipsing barely remembered haunts. Compensation for the horrible necessity of attending the bedside of a dying old man. I loathe sickness and death. When anybody is sick, I am overcome with a feeling of helplessness. I don’t know what to do, and if I did, I wouldn’t want to do it. Sickness nauseates me. For two long days I will be dutiful and son-like and then … escape. Maybe pop in on my way back for a final farewell, just in case Jenny writes. At least she won’t phone often — Jenny knows how much I dislike the phone, a foible I now recall that I share with my father. I am too cheap to get caller identification and all those extra things you can get these days, so I never pick up till the person starts to leave a message. Usually, I’m in the middle of doing something. How can one not be in the middle of doing something since things are being done every minute of the day? I am never sitting by the phone, wanting to talk to somebody. It’s always in the middle of dinner, or the middle of a movie, or in the middle of a dump. Very rarely, if it’s somebody I just love to talk to at any time, I pick up in the midst of a dump, but most of the time I convince myself that I could be out, and therefore might as well pretend that I am. The strange thing is, although everybody else I know has caller identification for the express purpose of screening their calls, they always sound surprised and offended if I pick up mid-call.

“I just wanted to call and let you know I’m back in town…”

Click.

“Hello, Jeremy?” Trying to sound breathless like I’ve just raced from the bathroom.

“What, you’re there? What are you doing, screening your calls?” Spoken in a hurt away, as though the length of time it took me to answer indicated indecision.

“No, no, of course not,” (why the hell shouldn’t I) “I was just in the middle of unprocrastinatable bodily functions.”

“What?”

“Isn’t that a word? Unprocrastinatable — impossible to procrastinate. I was taking a crap, my friend.”

“Oh.” He injects the word with immense doubt, and I maintain a frosty silence which conveys my outrage at having interrupted a crap for this jerk.

Luckily, Jenny believes she is one of the people I just love to talk to at any time. I maintain this illusion by picking up the phone every time I hear her voice on the answering machine. For her part, she respects my dislike of phones and seldom calls. If I stress my father’s similar hatred of phones, she won’t call much.

With such a pleasant holiday in mind, I am surprised at the weird feelings that overcome me every time I think about it. Sitting on the plane, willing my face to remain normal so that the mother beside me can relax now that her kid is asleep, I am overcome with anxiety about the coming days with my father. Why? And while we’re at it, why haven’t I seen my father since I was eighteen?

All I have are vague memories, and I have not dredged them up for twenty years. I sit back in my seat and try to recollect pieces of my old life, my childhood, my teenage years. There must be millions of things to remember. I close my eyes and concentrate. The mother beside me will think I am asleep. I imagine her digging her little fingernail into her front teeth to get at a strand of meat that has been stuck there since dinner. I wonder if it’s difficult for mothers to indulge in the personal attentions that I take for granted?

Drag my lazy mind back to the task at hand. Concentrate on the vague wisps of memory and they will sharpen. I regret the wine.

There was a time when he was driving me somewhere. Mother was almost always the one to drive me, even though she worked longer hours

at her nursing than he did as a professor. No doubt there was some justice to this, because she was the person who signed me up for piano lessons, swimming, soccer. I hated these extra-curricular activities. It was awful going out after dinner, wasting an entire evening after a never-ending day at school. Grant me the ability to allow my children to relax and do nothing with their evenings, should I ever knock Jenny up by mistake.

I remember that I didn’t want my father to drive me, and I sat by his side, unable to stare out of the window and dream like I did with my mother. Was this because I didn’t know whether he wanted to talk or not? Was I unable to relax for fear he would interpret my silence as discomfort? I longed to tell him that I liked to dream in the car, and hated to talk. Mother liked to talk, and I often had to tell her to be quiet, which is something I knew I wouldn’t be able to do with him.

Then something happened, maybe the tire went flat, and the car careened towards the side of the road before my father managed to slow it down and pull over. He slammed out of the car and marched around the back. I remember how my whole body tensed, and I felt this lump of fear in my chest. Fear of what? I didn’t know whether I should get out and help, so I remained glued to my seat, waiting. He wasn’t outside very long. Upon returning he smashed the poor door shut with equal violence. “This stupid fucking car,” he bellowed. His voice was aggressive. He did not use the word ‘fuck’ often and it sounded nasty. I was petrified.

That’s all I remember.

There was another incident, where my mother’s reaction sticks in my mind, though the incident itself is a bit hazy. My parents and I were out picking blueberries in the fields beside our farmhouse. Anything to do with the land made my father happy. Every so often he held up his little pan of blueberries.

“Look, I’ve picked dessert. See how Daddy provides for his family.”

This was a favourite theme of his. Born and brought up in London, he had spent his entire adulthood moving from one city to another, teaching at universities. He taught at UBC for several years, then when I was about six we moved to a suburb of Halifax, where he had a job at Dalhousie University. He had a joke about that. “This Frenchman once came up to me in the street, and asked me ‘Where Da Lousy University?’ ‘Do you mean Dalhousie?’ my father asked. “Da Lousy University! Dat’s what I said!” the Frenchman cried. My father concluded that the Frenchman’s appellation was more appropriate than his, and showed him where to go.

Turn Us Again

Turn Us Again