- Home

- Charlotte Mendel

Turn Us Again Page 3

Turn Us Again Read online

Page 3

I must remember not to sprinkle my language with “fuck,” like I do at home.

Old people frequently smell funny, like they no longer have the energy to reach those difficult nooks and crannies that emit the least acceptable aromas. My father said he was dying. I don’t even know what he’s dying from. Maybe it’s skin cancer, and his whole face will be eaten up by some malodorous wound, like the mother in Mad Shadows.

While I stand there dredging up the courage to cross the tiny courtyard and knock on the door, it opens and a little old man stands there. My first shock: I remember my father as huge. He peers out at me. “I expected you over half an hour ago,” he snaps, and then turns around and disappears inside, leaving the door open.

Am I disappointed or relieved by this welcome? Even though I had been dreading an excess of physical affection, this reunion between father and son doesn’t seem adequate. So when I discover my father waiting by the coat rack just inside the door, I drop my case and embrace him. I hold him longer than I thought I’d ever hold an old person, and in the end it is he who moves away. He does not smell, nor cling in gratitude at my embrace. He feels much smaller than I remember, frailer. Maybe all this repulsion/attraction stuff hasn’t got anything to do with old or young, but is simply a case of my own perverse nature. If I feel the other person wants to touch me, I recoil, but if they have no intention of touching me, then I begin to fancy a hug. I hope this journey is not going to involve discovering a whole bunch of unsavoury truths about myself.

As my father draws away I look into his face and see that I have provoked tears. He turns away and ambles down the corridor, which leads to a small, dark kitchen at the back of the house.

“You must be tired after your trip. Sit down, I’ll make you a cup of tea.”

“No really, let me make it for you. How do you feel?”

“I feel fine. This is my house and I’m making the tea. At least on the first day.”

His voice sounds the same, his brusqueness rings a bell too. I want to be glad that he’s so straightforward, rendering mind games unnecessary — no need to guess what the other person wants from you. But there is a stirring of discomfort, because he can be so unpleasant, and I have gotten used to gentle, predictable Canadian behaviour.

He bustles about, boiling the kettle, putting some bacon in the frying pan, taking the eggs out of the fridge and placing them beside the sizzling pan. Everything is imbued with a strange combination of familiar and unfamiliar. I remember how my father always heated up the eggs before cracking or boiling them, insisting that they needed a gradual transition from cold to hot. He also insisted that English bacon was better than Canadian bacon. I believed him and was his joyful accomplice every time we came through customs toting bags chock a block full of English bacon. Now I prefer crispy, fatty Canadian bacon. Even the gas fire, with the inconvenience of elusive matches, evoked memories: my father kneeling before the hearth at our Nova Scotia farmhouse.

“Do you remember how you tried to save matches every morning when you were lighting the fire? It used to take you ages, but you’d find a spark from the night before and tease it with some paper until it caught. You were so proud that you’d saved a match.”

It is the right thing to say. My father ceases his activities and smiles.

“While you used to sit there informing me how much a match costs. As though that had anything to do with it.”

“So how are you, anyway, Dad?” The ‘Dad’ feels strange, at first.

“I’m fine. How are you?”

“I mean, are you feeling OK, from a health point of view?”

“I’m fit as a fiddle, for a man of almost eighty. We are blessed with longevity in our family.”

Yes, I want to say, but what about the fax that said you were dying? It’s uncomfortable to ask personal questions of this nature when it’s obvious my father wants to avoid the subject. At least it’s not face cancer.

My father places a cup of tea and a plate of bacon and eggs before me. Everything is how I like it. There are two pieces of toast, dripping with butter. One bears two pieces of crispy bacon and an egg with the yolk just a bit soft. The second bit of toast is spread liberally with jam. I am suddenly happy. “It’s wonderful to see you! There’s so much between us…” I’m thinking about the perfection of my tea and my bacon and eggs. Jenny never gets it right. There’s never quite enough sugar in my tea or butter on my toast. As soon as I say it, I feel that it is inadequate, that my father will think I’m an idiot. I remember living a large part of my childhood worried that he would think this. Instead he says, “We are father and son.”

And I am consumed with guilt that I abandoned him.

He asks me about my life, and I tell him about my job and Jenny, careful not to swear. I want him to think my job is interesting, so I make it sound like a big deal.

“I design online courses for the web. I’m called an instructional designer. You can do marvelous things these days — animations, video, photography. I have to find a way to convey the teaching point in the simplest way with text and a visual element.”

“What are the subjects of the courses?”

Yes, well, I kind of hoped he wouldn’t ask that, just assume that I’d followed his footsteps and gone into education. “Technical things, Dad. I work for a telephone company.” I searched my brain for the most impressive course I had done. “It’s varied, anything from ergonomics to broadband, how high speed internet works. I learn a lot of different things.”

My father, a professor of English literature who taught books that he loved, doesn’t look too impressed.

“I want to write a book,” I say. “I would like to make a living from writing, but it takes some time to get started.”

“You remember it took me twenty years to write my book?” My father laughs, “Starting is the easy part.”

“Long after you’d published your book, you would say to me, ‘Will I ever publish my booky?’ and I would yell back, ‘You’ve already published it.’”

“Hats off gentlemen,” we shout simultaneously, and laugh. We always used to say that when we toasted the publication of my father’s book. I feel full of affection for this man, my father. Of course I need to know about his illness, even if it feels uncomfortable. I take a deep breath.

“Dad, your fax said that you were dying.”

He picks up a sugar cube carefully in the tiny tongs, without answering.

After an unbearable minute of silence, I try again, speaking very gently. “Dad?”

“Yes?”

“What is the … nature of your sickness?”

He waves the tongs dismissively. “Apparently there’s an uncouth rabble of cells breeding like rabbits somewhere in my innards. Cancer, you know. I wish my book had done better. It deserved to.”

“But Dad, how bad it is? Do you feel ill?”

The tongs fall against the sugar bowl with a little clatter. “The subject of my illness bores me. I didn’t want you here so we could natter on about cancer ad nauseam, and I will certainly regret contacting you if you go on and on and on about it.”

Tension churns in my stomach again. We’d been getting along so well. How stupid I’d been to annoy him. I wrack my brains for a safe subject.

“You’re right about your book. It was brilliant.”

He merely grunts.

A note of desperation creeps into my voice. “Do you remember that time at the beach for Mum’s birthday? You started to sing ‘Three Little Fishies’ and Mum and I laughed and laughed.”

That does it. My father throws back his head and his rich baritone flows out.

Down in the meadow in a little bitty pool

Swam three little fishies and a mama fishie too

‘Swim’ said the mama fishie, ‘Swim if you can’

And they swam and they swam all over the dam

Boopboopdit-tem dat-tem what-tem Chu!

Boopboopdit-tem dat-tem what-tem Chu!

And they swam and they swam all over the dam.

His head bops around as he sings, he closes his eyes, and I am lost in the strangest sensations from my past.

“Then Mummy lost the ring you’d given her, and we searched all along the beach. We never found it, and it was an invaluable ring that was originally your mother’s. Irreplaceable.”

Again, a frisson of fear as I recalled the white, strained face of my mother, desperate to find the ring. But my father hadn’t said anything at all, just never mind. Have I wronged this old man sitting opposite me? Surely it is outrageous to abandon the parents who have given you life, returning to the fold only when they are dying? The ultimate in selfishness.

“Father, I cannot justify why I haven’t been in touch. I am a rotten son.”

“I quite understand.”

What does he mean he quite understands? What is there to understand? My behaviour is selfish and unforgivable. I don’t understand what he is understanding.

After our meal my father takes me out to see the garden. It is as I thought — there is a decent-sized plot around the back, private, with tall brick walls on each side and a profusion of flowers. I express my admiration, and my father takes me around the entire circumference, explaining the name and history of each flower on the way. This is an interminable process, and I am bored, but I make the appropriate noises. All this takes a lot of energy, and I am starting to feel exhausted. After what seems like hours in the garden, we re-enter the house, and my father makes another cup of tea and brings out a tin of chocolate biscuits.

“Can I smoke here?”

“Of course. After our tea I am going to bed. I’m U.E.”

U.E. — utterly exhausted. A favourite expression of my father’s. Of course he is exhausted too. The way that our energy drains away in the company of other people is another shared trait.

I cannot sleep, despite the fact that I have been travelling all night. I twist and turn, trying to justify my behaviour. I cannot believe myself, wonder how I’ve lived with myself. Every aspect of his lonely life and small pleasures — the bacon and eggs, the chocolate biscuits, the garden — smites me. How did I become so selfish?

I determine to bring up the death of my mother at dinnertime, to see if it can shed any light on the reasons for the annulment of our relationship. Yet even while these castigating thoughts berate me, I calculate the amount of time that I can reasonably stay in bed and how soon I might retire there again after dinner. How many hours of this incessant draining of energy, caused by the presence of my poor father? I am U.E. I must go off on a little trip by myself.

The bracing effects of my rest have evaporated by dinnertime. After talking all afternoon, only venturing outside once for a short walk, I am once again drooping with desperate fatigue. My father does not allow me to help with the dinner. He says he has prepared everything over the past week. He takes ages in the kitchen while I ponder my role. It is a strange beginning for a son who’d assumed he’d be looking after his sick father.

The dinner ritual is strangely familiar. Pre-dinner drinks and cigarettes. Then roast beef, mashed potatoes, peas, Yorkshire pudding, followed by meringues and cream. A meal my mother might have made.

“Do you miss Mum?”

“That’s a stupid question. I’m all by myself.”

I glance at my father. He is exhausted too and might not be able to contain his irritation for much longer.

“I think I will go right up to bed after dinner, if you don’t mind. I didn’t manage to sleep this afternoon, and of course it was a night flight.”

My father smiles. Relieved? Is he wondering, as I am, how he will get through this visit, these endless days of exhaustive talk?

“I don’t know what you had in mind Dad, but depending on your state of health, I was planning to travel around a bit. I want to spend time with you, of course, but I don’t want to exhaust you. I can see you are tired.” This is rather clever, making the planned briefness of my stay a result of consideration, instead of selfishness.

“This might be our last time together, and I would like to see you as much as possible. If you think my exhaustion springs from hosting duties, I don’t plan to cook like this all the time. It’s important to make a little fuss on the first day. I’d be happy if you went out and amused yourself during the daytime, as long as you come back in the evenings so we can sup and talk together.”

“Of course. That sounds great.”

‘You are so fucking honest,’ I think to myself, ‘you just state your wants.’ In one way that is so much better than my devious wheeling and dealing. In another way it makes it difficult for me to state my needs, unless they tally with yours. That is my fault, for not getting in there first. But hadn’t I done that? Hadn’t I said I wanted to travel? I feel confused. I can’t remember. I see my planned trip threatened and feel determined to save it, wondering why I cannot blurt out a compromise. The feelings that hinder me in this inexplicable way prompt me to return to the subject of my mother.

“Do you often think about her death?”

“Not her death. Our life together. I think about it all the time. I think about how strange it is that a person can need, rely on, and love someone so much, yet spend their whole time trying to force that person into a mould that they can understand and control. Is it to diminish the fear that the person will leave them? I believe your mother would have left me, once you had gone.”

“Oh, surely not. There was a lot of love there.”

“I thought so. We had our ups and downs. I know that I am a difficult man. Of course there were some very sad episodes, usually when I was drinking. I always drank too much, it did our family irremediable harm. But I can count such episodes on one hand, and I thought there was happiness to balance them.”

I thought of the wrist spraining, and the shouts, and singing ‘Three Little Fishies’ on the beach.

“There was enough happiness to balance them. Of course there was.”

“I am so glad to hear you say that. Your mother did not think so, but I am so glad that the happy times balance the hard times in your memory.”

“I’m sure they did for Mum as well.” I look at this sad, defeated man and feel sorry for him. He is a fine father, a noble man. I’m not in a position to criticize him after my conduct as a son.

“No, they didn’t. She often felt down. Our connubial life crushed her instead of uplifting her. She was not a brilliant woman, you know, and from the beginning I assumed the role of teacher, pompous enough to think I might enlighten her. Perhaps later on I wanted her to conform to modes of behaviour that would adapt to my needs, recognize that my needs were predominant because I was supporting the family. My life was harder, and my genius had to be nurtured and cared for, my faults forgiven, my temper smoothed away. Perhaps in our struggle towards our respective ideas about how married life should be, her confidence suffered. I forced her to submerge her true self.”

My father takes a long swig of his beer. I find myself wincing when he talks of his genius. It seems so pathetic, now that I’m an adult. When I was young I accepted his pontifications. The world was full of dolts and Nova Scotia had its fair share, but lacked its fair share of intellectuals — that slice of society in which my father revelled during his student days at Cambridge.

But now it sounds ridiculous. People just don’t talk in terms of superiority and genius — it isn’t politically correct. And I resent my mother not being included in our elite group. In my memory, she does not occupy the position of Caterer to the Needs of Genius. Rather, she embodies all that is warm, giving, selfless; a pure creature of the heart while my father is a creature of the head — neither being better than the other. “Do you remember how Mum used to quote the Bible?” I say in an attempt to change the subject. �

�That psalm she used to say every time I was down in the dumps…it’s on the tip of my tongue…”

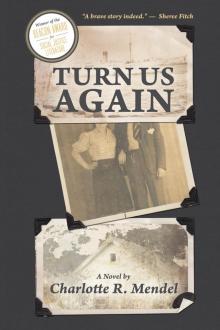

“Psalm 80. ‘Turn us again oh God, and cause thy face to shine; and we shall be saved.’”

“That’s it,” I cry, delighted. “I can almost hear her saying it! She said it made her feel hopeful.”

My father lays his empty beer mug on the table and continues as though I had not spoken.

“Your mother wrote a manuscript. It is written like a novel, in the third-person — perhaps she nurtured private dreams of publication. I found it after her death, when I was sorting through her things. At first … it upset me terribly. I wouldn’t have dreamt of showing it to anyone. Recently, when I learned of my sickness, I thought I only had two choices: destroy the manuscript or leave it for you to find. Both choices felt uncomfortable. Then I thought, what if Gabriel reads the manuscript while he is here, with me? Instead of becoming a negative legacy, it could become the basis of discussion and mutual understanding. ”

He waits for my reaction, and I manage a nod.

“It’s important to me that you read this manuscript. I want to see whether you still maintain that happiness balanced the bad times after you’ve read it. I want to explain my point of view whenever you feel … confused. Then I can die knowing that I have left a legacy that is not wholly negative.”

He ambles upstairs and returns with a faded, yellow stack of papers. I take it gingerly, reaching out with both hands.

“This is going to be weird.”

“An insight from your mother’s perspective. Please talk to me while you read it. Ask me to explain. You must hear my point of view, because I do not have twenty years to finish this ‘booky.’”

Later that night I lie in bed and hold the manuscript in my hands. My mother wrote this manuscript. It seems incredible. Will she be a horrible writer? Will I feel embarrassed? Will the truth set me free?

The Unexamined Life Is Not Worth Living

—Socrates

Turn Us Again

Turn Us Again